The use of ornament in the garden can have a big impact. Ornaments provide focal points, reinforce the style of the garden, make us pause and think. They offer a delightful way to introduce personality into the garden. One of my favorite gardens uses flying pigs...

Read MoreFarm to table: Fit for a queen

There are many types of beautiful gardens, but none are more different than the formal garden and the vegetable garden.

The formal garden is primarily ornamental. Geometry, symmetry, constraint, and an axial relationship to a main structure rule the design. Clipped plant material reminds us of our desired supremacy and control over nature. Statues celebrate great past accomplishments, connecting us to a broader historical context. The formal garden is soothing in its repetition and orderliness; it feels sheltered from the dangers of the natural world.

The vegetable garden is primarily practical. Meant for physical nourishment. Here is an immediacy that comes from the planting, growing, harvesting cycle. It is meant for a hard day’s work and a good nap at the end of the day. In return we get food and sustenance. It too provides a sense of shelter, though mostly intended to protect precious crops.

Nowhere do these two garden styles contrast with greater impact than at the Chateau de Versailles. I always thought of Versailles as an iconic formal garden. Miles of straight paths radiate from the Palace into a series of formal gardens, many with grand water features. This garden screams power, money, destiny. The vistas into the horizon are remarkable in a “how did they carve this out of swamp and woodland” way; but the effect is also intimidating. I felt small in the face of it.

After hours of walking through these formal gardens, the transition into the Queen’s Hamlet brings welcome relief. Behind the Petit Trianon sits a traditional English picturesque garden where curved paths follow a naturalistic stream. Each turn opens up a new view until finally a large lake frames a French rustic village.

It feels as if you’ve stumbled onto a small town. Without the gravel path leading toward it and it being on the official garden map, I might have stopped at the view so as not to disturb the families living there.

From some angles the composition is too perfect, like a movie set or theme park. Every piece of the design is intentional. A few man-made toad ponds blend into the meadow and provide part of the sound track.

Marie Antoinette commissioned this garden in 1783 as a retreat from the pressures of the Court. The garden was built by architect Richard Mique and painter Hubert Robert at an estimated cost of $5 million (in today's $'s).

The garden is an imitation of a rustic French village, a series of thatched roof houses each has its own gardens framed by hornbeam hedges and chestnut trees, and planted with useful cabbage, artichokes and lettuce. There are climbing vines on most buildings, flowers for cutting, and simple flowerpots. There’s an orchard and vineyard and small barn for farm animals. This was a working farm run by a real farmer who put food onto the royal table, but the main purpose of this garden was to provide Marie Antoinette a place to relax with friends.

I couldn’t help but feel a philosophical struggle at Versailles between the vast series of extravagant formal gardens that celebrated legacy and big government on one side of the Petit Trianon, and on the other side this (also extravagant) idealized rustic place that celebrated simple farm life. Did I want to stay in the warm, country village or go back to the grandeur of the Palace? Perhaps a metaphor for the struggle going on in France that led to the French Revolution? Marie Antoinette barely enjoyed any time in this garden. By the time it was completed, the Revolution had begun.

See more posts about the gardens at Versailles here.

The vegetable garden I am planning this year won’t look anything like this, but it is fun to dream.

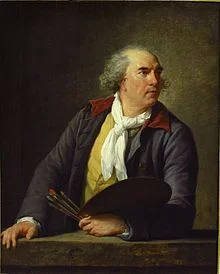

Hubert Robert by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. Source: Louvre.

Drawing of Richard Mique holding garden plan, unknown artist (courtesy of Musée Carnavalet, Paris)

Controversy in the garden, 1882

"During the last twenty years Europe has been swept by a mania for sacrificing natural scenery to coarse manufactures of brilliant and gaudy decoration under the name of specimen gardening; bedding, carpet, embroidery, and ribbon gardening, or other terms suitable to the house-furnishing and millinery trades. It was a far madder contagion than the tulip-mania ... of our youth."

- Fredrick Law Olmsted, The Spoils of the Park, 1882

Gardeners as a group are a friendly bunch. However, there are a few topics that can be polarizing. Arguments about formal vs. informal, native vs. exotic, natural vs. man-made, annual vs perennial, are common.

Full copy available on books.google.com

In the 1800’s, the gardenesque style arranged exotic plant specimens to show off their full potential. In some cases this was done with a single plant or cluster; at other times brightly colored plants were combined in patterns that resembled carpets, embroidery, and stripes.

When the picturesque style had a resurgence in popularity in the 1800’s, some designers thought that these patterned plantings had gone too far.

One example can be found in the quote above. I think it’s clear where Olmsted stands on this issue.

Nonetheless, gardenesque bedding schemes remain popular. Like our attraction to shiny objects, we can hardly resist the sheer explosion of color and pattern. A few examples above from London's Hyde Park, Chateau de Versailles in France and Keukenhof in the Netherlands continue to draw large numbers of visitors.

See more gardenesque gardens here.