There are many types of beautiful gardens, but none are more different than the formal garden and the vegetable garden.

The formal garden is primarily ornamental. Geometry, symmetry, constraint, and an axial relationship to a main structure rule the design. Clipped plant material reminds us of our desired supremacy and control over nature. Statues celebrate great past accomplishments, connecting us to a broader historical context. The formal garden is soothing in its repetition and orderliness; it feels sheltered from the dangers of the natural world.

The vegetable garden is primarily practical. Meant for physical nourishment. Here is an immediacy that comes from the planting, growing, harvesting cycle. It is meant for a hard day’s work and a good nap at the end of the day. In return we get food and sustenance. It too provides a sense of shelter, though mostly intended to protect precious crops.

Nowhere do these two garden styles contrast with greater impact than at the Chateau de Versailles. I always thought of Versailles as an iconic formal garden. Miles of straight paths radiate from the Palace into a series of formal gardens, many with grand water features. This garden screams power, money, destiny. The vistas into the horizon are remarkable in a “how did they carve this out of swamp and woodland” way; but the effect is also intimidating. I felt small in the face of it.

After hours of walking through these formal gardens, the transition into the Queen’s Hamlet brings welcome relief. Behind the Petit Trianon sits a traditional English picturesque garden where curved paths follow a naturalistic stream. Each turn opens up a new view until finally a large lake frames a French rustic village.

It feels as if you’ve stumbled onto a small town. Without the gravel path leading toward it and it being on the official garden map, I might have stopped at the view so as not to disturb the families living there.

From some angles the composition is too perfect, like a movie set or theme park. Every piece of the design is intentional. A few man-made toad ponds blend into the meadow and provide part of the sound track.

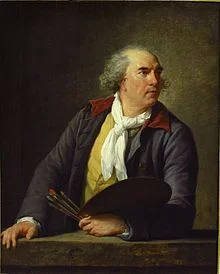

Marie Antoinette commissioned this garden in 1783 as a retreat from the pressures of the Court. The garden was built by architect Richard Mique and painter Hubert Robert at an estimated cost of $5 million (in today's $'s).

The garden is an imitation of a rustic French village, a series of thatched roof houses each has its own gardens framed by hornbeam hedges and chestnut trees, and planted with useful cabbage, artichokes and lettuce. There are climbing vines on most buildings, flowers for cutting, and simple flowerpots. There’s an orchard and vineyard and small barn for farm animals. This was a working farm run by a real farmer who put food onto the royal table, but the main purpose of this garden was to provide Marie Antoinette a place to relax with friends.

I couldn’t help but feel a philosophical struggle at Versailles between the vast series of extravagant formal gardens that celebrated legacy and big government on one side of the Petit Trianon, and on the other side this (also extravagant) idealized rustic place that celebrated simple farm life. Did I want to stay in the warm, country village or go back to the grandeur of the Palace? Perhaps a metaphor for the struggle going on in France that led to the French Revolution? Marie Antoinette barely enjoyed any time in this garden. By the time it was completed, the Revolution had begun.

See more posts about the gardens at Versailles here.

The vegetable garden I am planning this year won’t look anything like this, but it is fun to dream.

Hubert Robert by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. Source: Louvre.

Drawing of Richard Mique holding garden plan, unknown artist (courtesy of Musée Carnavalet, Paris)