Garden ornaments provide a way to add personality to the landscape, share a personal passion, and lend an exotic touch to the garden.

In the 1770’s the Kew Royal Botanic Garden added its own exotic garden ornament in the shape of a full sized Chinese-style pagoda. At 160 feet tall, it can be seen from miles away.

It is nestled inside a picturesque intersection of four avenues where peacocks greet visitors. (Peacocks, the national bird of India, also add an exotic element.) There are multiple opportunities to see framed views of the building. This giant garden folly serves as a focal point. It draws visitors from all sections of the garden, who look at it with a sense of puzzlement and awe: “what is that? how did it get here?” The structure is also a window into a far away ancient culture. When it was built, it would have been most visitors’ only exposure to the Far East.

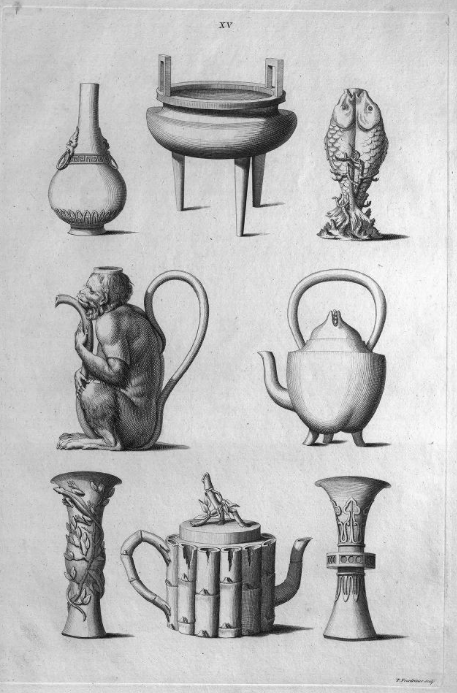

The story of how this pagoda got to England reflects the larger connection between Europe and China in the 1700’s. Consumers were already familiar with Chinese goods like silk, porcelain, and tea. Expositions and travel accounts launched a craze for all things inspired by China – also known as Chinoiserie.

So when Prince George – later King George III - decided to honor his mother with a memorable Chinese garden structure at Kew in 1761, he turned to architect William Chambers.

Chambers was perfect for the commission. He spent time in Canton, China as part of his job with the Swedish East India Company. While there, Chambers studied Chinese architecture and landscapes and put together the material for his 1757 book Designs of Chinese Buildings. It included a chapter called “Of the art of laying out gardens among the Chinese.” His writing tends to be clinically descriptive, although a few of his statements are false or over generalizations - “the Chinese are not fond of walking” and “the Chinese are not well versed in optics.” Above all, he clearly loved Chinese design: “the art of laying out grounds, after the Chinese manner, is exceedingly difficult, and not to be attained by persons of narrow intellects… putting them in execution requires genius, judgment, and experience; a strong imagination, and a thorough knowledge of the human mind."

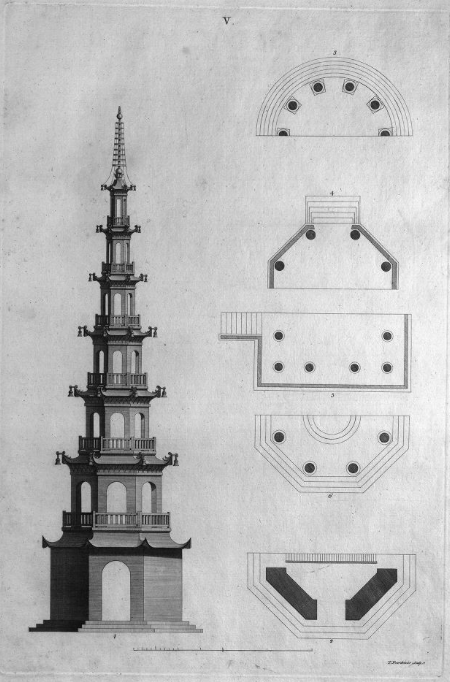

About pagodas, Chambers wrote: “The towers called by the Chinese Taa, and which Europeans call … pagodas, are very common… In some provinces … you find them in every town… In regard to their form, the Taas are all nearly alike; being of an octagonal figure, and consisting of seven, eight, and sometimes ten stories, which grow gradually less both in height and breadth all the way from the bottom to the top. Each story is finished with a kind of cornice, that supports a roof, at the angles of which hang little brass bells.”

It was this expertise that led him to be selected to design the Kew pagoda.

His 10-story structure was a sensation; many thought that it would collapse. It must have been quite a site, for in the images above, we only see a shadow of its original self. The ends of the eaves were decorated with iron dragons and colored glass and the top was gilded.

Rumor has it that the dragons were sold off to pay for royal gambling debts, but most people believe that they were just too costly to maintain.

Kew has just started a 2-year renovation that will restore the pagoda to its 1760’s glory. Time to start planning a visit for 2018!

Do you have an exotic folly in your garden?

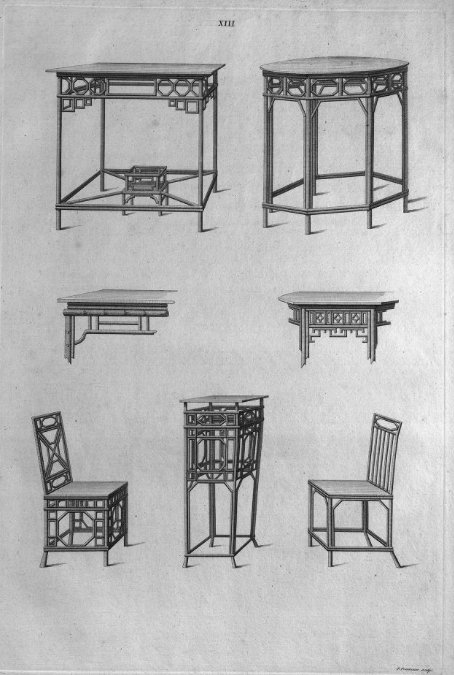

Excerpts from Chambers 1757 Designs of Chinese Buildings, a book that fueled an interest in all things Chinese.