“Fight for a just cause; Love your fellow man; Live a good life” was the favorite credo of the creators of this quintessentially American gilded age country house and garden. The first 2 letters of each phrase, FI-LO-LI, form the name of this special place. It also is an apt description for the garden today….

Read MoreGarden magic

Line, form, texture, scale, balance, emphasis, and repetition are critical to create beautiful garden spaces. Together these are the building blocks toward a unified design and need to be chosen carefully for a design to feel right.

However, during my recent trip to San Francisco’s Japanese Tea Garden, I was struck by the importance of small details in good garden spaces. These don’t hit you over the head at first; they often go completely unnoticed. I believe that even if we only absorb them sub-consciously, these details create magic in the garden, making the ordinary extraordinary.

One great example of this for me is the series of stepping stones that cross the small stream pictured above.

On one level, the stones are just a way to cross from one part of the garden to another.

At closer inspection, these are gardens unto themselves, full of mosses and ferns; miniature gardens in the midst of a larger space. And there is something powerful in the contrasting layers: the hard, smooth top of the stone honed by unforgiving foot traffic; the dark waters of the stream below; and in the impossibly small middle space a lush green garden.

This Japanese Tea garden is the oldest Japanese public garden in the US. Japan was only opened to the West in 1853 and by the turn of the century all things Japanese were popular. This garden is one example. In an effort to introduce Americans to Japanese culture, the 1894 San Francisco California Midwinter International Exposition included a Japanese Village exhibit.

Landscape architect Makoto Hagiwara expanded this work into a 5-acre garden and his family worked on the garden until 1942. At that point, the family was forced to leave their home for an internment camp in Utah. During the war the garden was renamed the Oriental Garden and many of the elements Hagiwara introduced were lost. In 1952 the name reverted back to the Japanese Tea Garden.

Balance, harmony, form, texture are important for sure. But let’s not forget to appreciate the small details that make a good garden great.

See more Japanese garden stories here.

Cloister garden: Mission style

Today we appreciate cloisters for their ability to create soothing sheltered spaces for observation and contemplation; for providing simple gardens full of the useful flowers, vegetables and medicinal herbs; and for including water, essential for life. These elements create a powerful contrast to the 24/7 pace of the modern world.

Historically, the cloister garden also played an important role in protecting those inside from physical attack and sustaining them during periods when they could not venture out. In 800 CE England the cloister provided protection from Vikings. In 1800 California, missions used the cloister design for protection from the native population.

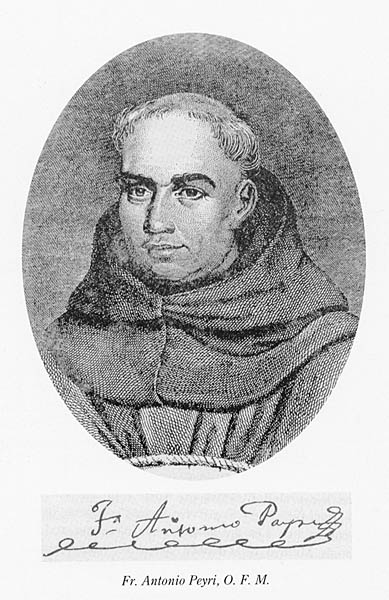

The garden pictured above is from southern California’s Mission San Luis Rey, in an area that was originally home to the Luiseño people. The mission was established in 1798 to extend Spain’s colonial claims. Its purpose was to teach the Luiseño "useful" trade skills and to preach Christianity. Life for the Luiseño under this scheme was hard and some organized raids on the mission in an attempt to close it. Fear of attack led to the church that we see on the site today, built in the 1810’s.

Master stonemason Antonio Ramirez designed and oversaw the construction, with Luiseño converts doing the work. The main walls of the church were 30 feet high and five feet thick. The garden is set inside the mission compound. Framed by deep covered walkways, there is a central well for access to water, areas for planting useful herbs, food, and flowers, and a grassy area where a few animals could be sheltered.

In 1830, the mission was the largest building in California. 3,000 Luiseño’s managed 50,000 livestock, and tended to crops of grapes, oranges, olives, wheat, and corn.

Disease played a key role in the loss of nearly half of the Luiseño population. Cave Couts, a prominent cattleman wrote to a friend in 1862, "Small pox is quite prevalent… six to eight per day are being buried --Indians generally." (From Richard Crawford’s “Fatal Funeral: Rancher Recounts 1863 Killing Over Fear of Smallpox”, LA Times.)

The mission fell into ruins in the 1850's and its restoration began with the arrival of Franciscan Father Joseph O’Keefe. Today the site is a National Historic Landmark and houses the Franciscan School of Theology, which prepares priests and lay women and men for shared ministry in the Catholic Church.

See more cloister garden stories here.